January 2024 has been a busy month for storm events, with Isha and Jocelyn being the latest storms to hit Ireland within 48 hours of each other last week. Since Storm season 2023/24 started, back in September 2023, Ireland has seen ten storms named, which feels like a high number of them. Let’s look at what’s behind this stormy autumn and winter so far.

Mainly, the jet stream

The position of the North Atlantic jet stream determines how many low-pressure systems move close to, or directly over Ireland each season. The strength of the jet stream and how each individual low-pressure system interacts with it determines whether these low-pressure systems intensify enough to become Atlantic storms.

Ireland, being a relatively small island on the edge of north-western Europe, has periods where the jet stream directs Atlantic storms towards it with high impacts, and periods when the jet stream directs Atlantic storms further north or further south with little or no impacts here. Many factors and global drivers that interact with each other in a complex way influence the position of the jet stream over the north Atlantic, making it very difficult to forecast accurately more than a week ahead.

The jet stream has been very active since August 2023, and positioned so that more Atlantic storms have been directed towards Ireland and the UK. After a relatively dry and cool first half of January in Ireland, with blocking high pressure in control, the North Atlantic jet stream intensified again over the last couple of weeks.

The purple colour in this animation shows the core of the jet stream as forecasted for this week, from today, Monday 29th January and until Sunday 4th February 2024. As the animation shows, its core is very close to Ireland or passing over it during most of the week.

Over the last couple of weeks, the intense jet stream, initiated by a large temperature contrast over the eastern part of the US, was slightly further north again compared to earlier in the season, and directed the low-pressure centres to the north of Ireland. The strongest winds of mid-latitude storms are usually on the southern side of the low pressure system, and as both Storm Isha and Storm Jocelyn centres moved to the north of Ireland, the strongest winds associated with these storms hit Ireland and the UK. Other named storms, such as Storm Ciarán, missed Ireland to the south, with the strongest winds hitting France and/or Spain instead.

Fig 2 – This graphic shows the low-pressure centre of Storm Jocelyn to the north of Ireland, as the southern part of the storm sees high winds hitting Ireland and the UK

Met Éireann climatologist, Paul Moore explains more:

“The position and strength of the North Atlantic jet stream determines the number and intensity of Atlantic storms that affect Ireland in any given storm season. The North Atlantic jet stream is driven by the temperature differences between the north and south and tends to be strongest in winter when the temperature difference is at its highest.

The variation in the North Atlantic jet stream from year to year and week to week is further influenced by complex interactions between many different components and drivers of the global weather system such as the North Atlantic seas surface temperatures, the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, the Madden-Julian Oscillation and the Stratospheric Polar Vortex in winter.”

How Storm Naming works

The practice of naming storms is a common one for meteorological service groups around the world, and is aimed at enabling consistent, authoritative messaging to support the public to prepare for, and stay safe during potentially severe weather events, and to enhance collaborative efforts between partner organisations.

Met Éireann has been naming storms since the 2015/16 season, together with the UK Met Office and later with the Dutch KNMI, which joined in 2019. These three national meteorological services constitute the “western” group of national weather services, and together they identify storms that could cause ‘medium’ or ‘high’ impacts in one of the three partner countries.

When a storm is forecast, usually the national meteorological service that expects the biggest impact from the severe weather, names the storm. Storm naming happens in conjunction with orange/red weather warnings, which could be for wind, rain or snow or a combination of these conditions. Those warnings are issued based on a combination of numerical criteria and the potential impacts foreseen.

If an intense Atlantic storm is not forecast to directly impact a country in the western group of national meteorological centres (UK Met Office, Met Éireann and the Dutch KNMI) but it is forecast to impact a country in the south-western group (which includes Spain, Portugal, France, Belgium and Luxembourg) then it will be named by the national meteorological service of one of those countries, from a different list of names to the one the western group is using this season. For example, on December 30th 2023 an Atlantic storm, named Storm Geraldine by Météo-France, caused yellow wind warnings to be issued for Ireland, but the strongest winds were forecast to impact northern France, which is why Météo-France named it (and when a met service names as a storm, the name is adopted by all other met services in Europe). The south-western group are also having a busy season with ten named storms so far in the 2023/24 season.

Ireland’s history of storms

The busiest storm naming seasons to date for Ireland were 2015/16 and 2017/18 both of which saw 11 named storms, including Ophelia in October 2017, named by the US National Hurricane Centre. Remarkably in 2015/16 all those 11 storms were named by the western group (Met Éireann, UK Met Office and KNMI). In contrast, 2022/23 was a quiet season, with only two named storms by the western group, Antoni and Betty in August 2023, and four in total affecting Ireland. These preceded a busy start to the 2023/24 season, which so far has seen ten named storms (from Agnes at the end of September 2023 to Jocelyn last week).

Several named storms affecting the same area in quick succession over a short period of time is not unusual, as evidenced by the occurrence of three named storms, Dudley, Eunice and Franklin in a space of four days, between February 16th and February 20th, 2022.

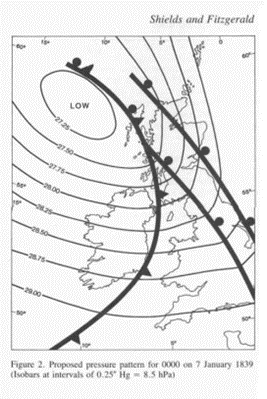

Of course, Ireland has a long history of vigorous Atlantic storms affecting the country long before storm naming officially began here in 2015. The winter of 2013/14 saw ‘an exceptional run of winter storms, culminating in serious coastal damage and widespread, persistent flooding’, as well as storm force winds on twelve different days during that winter. Looking further back, “Hurricane Debbie” in September 1961 and the “Night of the Big Wind” or “Oíche na Gaoithe Móire” in January 1839, are among the more famous examples of violent storms affecting the country.

Fig 3 – From “The Night of the Big Wind in Ireland, 6-7 January 1839”, Lisa Shields and Denis Fitzgerald, Irish Meteorological Service.

Does climate change have an impact on the number of storms?

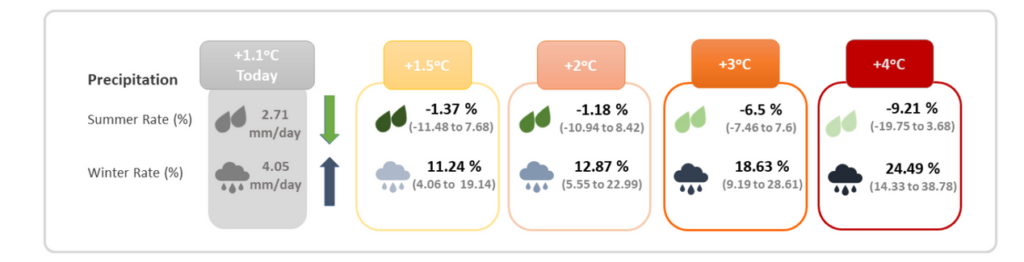

It is an established fact that human-induced greenhouse gas emissions have led to an increased frequency and/or intensity of some weather and climate extremes since pre-industrial time, particularly in relation to temperature and precipitation. However, it is currently unclear how the frequency and intensity of storms impacting Ireland will evolve with climate change, due to the large variability from year to year with no clear pattern emerging. There is high confidence, however, that maximum rainfall rates associated with extreme precipitation events will increase with warming.

Fig 4 – Change in seasonal precipitation (%) for Ireland under different levels of global warning, from Met Éireann’s TRANSLATE project

If you want to know more about storms, check our Storm Centre page.