If you travel to Erris in North Mayo, past the town of Belmullet and down the Mullet peninsula, when you run out of road and can travel no further, you are at Blacksod Point. Its key feature is the handsome square lighthouse, built in local reddish grey granite, upon which you will find a plaque linking Blacksod Point to the weather forecast for the invasion of Europe in 1944, D-Day.

But how does a small village on the western fringes of Europe, end up playing a small but key part in one of the most important events of the 20th century?

Blacksod weather station 1942, looking west towards the Stevenson screen with post office in the background. Photo: F.E.Dixon. Copyright: Met Éireann

The story revolves around Maureen Flavin and Ted Sweeny. Ted’s mother Margaret ran the post office and in 1922 she took over responsibility for the local weather station after the British Coast Guard was withdrawn. When war arrived, the demand for up-to-date weather observations grew, the telegraph was replaced by a telephone, and observations were expected to be delivered every hour, around the clock. Between running the weather station, the post office and, in Ted’s case, the lighthouse, an extra set of hands was sorely needed and in 1941, Maureen Flavin from Knockanure, North Kerry duly answered an advertisement for a job as a post office clerk. In 1939, a secret agreement was reached for the exchange of weather data between Ireland and Britain (Keane, 2012). In the 1940s weather forecasts were made subjectively by analysing the current weather based on weather observations and then extrapolating the state of the atmosphere at a future time. Forecasts depended much on the skill and experience of the forecaster in question and were only considered reliable for one to two days (Shields, 1987).

During the planning for the D-Day invasion, the Allies identified only a handful of opportunities in which the moon and tides were suitable for a seaborne landing on the heavily fortified coast of Normandy (Cornford, 1994) but the one factor they could not control was the weather. June 5th, 1944 was initially set as D-Day but due to the considerable logistics involved in gathering the largest armada ever assembled, the decision to proceed with the invasion had to be taken by the evening of the 3rd of June (Stagg, 1972). Operation Overlord was supported by the central weather forecasting offices of the British Met Office, the Royal Navy, and the U.S. Air Force. Group Captain James Stagg, who had worked for the British Met Office, was appointed chief meteorologist under supreme commander General Dwight D Eisenhower. Stagg’s role was to bring a measure of agreement between the different central weather forecasting offices and to advise the supreme commander and his commanders-in-chief directly (Stagg, 1972).

In the run up to the planned invasion, a string of small-scale low-pressure systems appeared in the north Atlantic (Moreby, 2022). Differences in predicting how these weather systems would develop and what the implications would bring to the Normandy landings, led to disagreements between the respective forecasting offices of the UK and the US. A key problem for forecasters in the run up to D-Day was their lack of knowledge of the development of low-pressure systems once they entered an area southwest of Greenland and northwest of Ireland (Stagg, 1944). At the time, in this area there were weather reports available from only two ships, supplemented by regular metalogical flights, which posed problems in accurately locating the oncoming weather systems, and determining their speed and development. To make matters worse, at a critical point on the morning of the 3rd of June, air pressure observations from one of these ships became unreliable (Stagg, 1944).

The 3rd of June 1944 was Maureen Flavin 21st birthday, and as she went about her work in the early hours of the morning, the weather was deteriorating due to the passage of a weak warm front, bringing with it persistent rain and drizzle, a drop in atmospheric pressure, and increased winds. In England, Stagg was no nearer to getting an agreement between the respective forecasting offices, with the Americans were of the view that a weak cold front would allow a ridge of higher pressure to build, giving a generally favourable outlook for the invasion period. In this prognosis, the pressure over the West of Ireland would soon show signs of rising. The British Met Office could not accept this diagnosis, and by way of emphasis, indicated that Blacksod Point had just reported a rapidly falling Barometer and force 6 winds (Stagg, 1972). These facts clarified to Stagg that the weather for the 5th of June was unlikely to be suitable and over the course of the day the pressure in the west of Ireland continued to fall and with it went any prospect that the weather in the channel would be settled for the foreseeable future (Stagg, 1972). Stagg duly reported this to General Eisenhower and his commanders-in-chief, who made the decision to provisionally postpone the invasion for 24 hours.

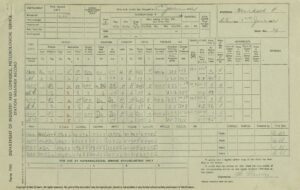

An observation sheet completed by Maureen on 3rd June 1944

On the morning of the 4th of June, observations at Blacksod showed the pressure beginning to rise with the unforeseen passage of a cold front, which was much further south than had been expected (Shaw & Innes, 1984). The passage of this cold front indicated a substantial change in the situation as it was understood previously. A ridge of higher pressure was now expected to build in its wake, bringing a short period of more favourable but not ideal weather conditions for the invasion (Stagg, 1972). Armed with this information, Eisenhower made the decision to proceed with the invasion on June 6th, and the rest is history. Had he waited for the next opportunity, the fleet would have sailed into the worst storm in the channel for 40 years and would certainly have failed. Eisenhower afterwards wrote to Stagg saying, “Thank the gods of war we went when we did!” (Stagg, 1972).

After the war, in 1946, Ted and Maureen married, and When Ted’s mother retired, Maureen took over the running of the post office and weather observing duties. These continued until 1956 when a full-time weather station was opened near Belmullet. It was only at this stage that they were told about the significance of their observations to the D-Day landings. Maureen Sweeney (nee Flavin) passed away in December 2023 at the age of 100, she was predeceased by husband Ted in 2001. Maureen was honoured by the United States government in 2021 with a medal, acknowledging how her observations led to the delaying of the critical landings by 24 hours, thus ensuring their success and saving the lives of countless US soldiers during the operation. A proclamation of her achievements was placed in the US Library of Congress (Met Eireann, 2023).

Maureen and Ted Sweeney on their wedding day. Copyright: The Sweeney Family.

References:

Cornford, S. (1994) With Wind and Sword. UKMO.

Met Éireann (2023) Maureen Sweeney (1923-2023) Met Éireann – The Irish Meteorological Service.

Keane, T. (2012) Establishment of the Meteorological Service in Ireland. The Foynes Years, 1936-1945. Dublin: Met Éireann.

Moreby, S. (2022) D-Day Analyses, ECMWF. Available at: https://www.ecmwf.int/en/research/projects/era-clim/d-day-analyses (Accessed: 30 May 2024).

Shaw, R. and Innes, W. (1984) Some Meteorological Aspects of the D-Day Invasion of Europe 6 June 1944. Boston, Massachusetts: American Meteorological Society.

Shields, L. (1987) The Irish Meteorological Service: The First Fifty Years, 1936-1986. Dublin: Met Éireann.

Stagg, J.M. (1944) Report on Meteorological Implications of D-Day. UKMO.

Stagg, J.M. (1972) Forecast for overlord; June 6, 1944. by J. M. Stagg. New York: W. W. Norton.